Will Eventually Bring the Ocean Back to Equilibrium and Be Able to Absorb Co2 Again

The idea seemed simple enough: the more carbon dioxide that people pumped into the atmosphere past burning fossil fuels, the more the oceans would absorb. The ocean would continue to soak upward more and more carbon dioxide until global warming heated the ocean plenty to ho-hum downwardly ocean apportionment. Water trapped at the surface would go saturated, at which bespeak, the ocean would irksome its carbon uptake. To oceanographers of 30 years agone, the question was less, how will human emissions modify the ocean carbon bicycle, and more, is the body of water carbon bike irresolute yet?

The question matters considering if the ocean starts to take up less carbon because of global warming, more than is left in the atmosphere where it can contribute to additional warming. Scientists wanted to understand how the sea carbon cycle might alter and so that they could make more accurate predictions about global warming. Thus motivated, oceanographers began a series of inquiry cruises, trolling across the Pacific from Nippon to California, from Alaska to Hawaii, and through the Due north Atlantic from Europe to Northward America. On shore, others developed computer models.

One of the largest unknowns in our understanding of the greenhouse effect is the role of the oceans as a carbon sink. Much of the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels is soaked up by the oceans, but changes in the climate are altering this assimilation in surprising ways. (Photograph ©2007 *Fede*.)

After 30 years of research, the question itself hasn't changed, only the reasoning backside it couldn't exist more different. Oceanographers started out wanting to know if the ocean was keeping upward with the corporeality of carbon dioxide people are putting into the atmosphere. Instead, they found that people aren't the but players changing the sea carbon cycle. Over decades, natural cycles in weather and ocean currents alter the rate at which the ocean soaks up and vents carbon dioxide. What's more than, scientists are beginning to find evidence that human-induced changes in the atmosphere also modify the rate at which the body of water takes upwardly carbon. In other words, it turns out that the world is non a unproblematic identify.

The Measured Ocean

The group surrounds a circular cluster of instruments and 36 iii-human foot-alpine PVC (plastic) bottles, taking turns extracting sea h2o from the bottles, assembly-line style. It is a deliberate, well-ordered procedure. The glass sample bottles fix bated for oxygen samples are filled outset, followed by the massive syringe meant for cfc (freon) samples, and so on, until ten to fifteen different samples take come up out of each bottle. Everyone has a task and a identify. Information technology'southward a social result, a pause from the lonely hours each volition spend in his or her lab analyzing the samples before the next batch is hauled out of the ocean. It might even exist fun. Except that it's late winter. In the North Pacific. And they are on the deck of a ship, looking at the aforementioned faces that they've seen twenty-four hour period after mean solar day for four weeks or more, and they'll be repeating this procedure again in some other xxx nautical miles.

For more than than 30 years, research ships have cruised the globe'due south oceans, measuring carbon dioxide concentrations, bounding main temperatures, winds, and other properties. The map shows the paths of research cruises conducted as office of the World Climate Research Program's Climate Variability and Predictability project. Cruise measurements—along with those from buoys, drifting floats, orbiting satellites, and land-based atmospheric condition stations—are beginning to reveal long-term trends to ocean researchers. (Map by Robert Simmon, based on information from Dana Greeley, NOAA.)

"It's pretty barbarous," says Richard Feely, with the air of a veteran who thoroughly enjoys his work. An oceanographer who studies the ocean carbon cycle at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, he's been at this sort of thing for almost twoscore years. Feely is i of a community of oceanographers who have been monitoring Globe's oceans for decades, trying to figure out how much homo-released carbon dioxide the ocean has been soaking up.

For eons, the world's oceans have been sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and releasing it again in a steady inhale and exhale. The ocean takes upward carbon dioxide through photosynthesis by plant-like organisms (phytoplankton), as well as by simple chemistry: carbon dioxide dissolves in h2o. It reacts with seawater, creating carbonic acid. Carbonic acid releases hydrogen ions, which combine with carbonate in seawater to form bicarbonate, a form of carbon that doesn't escape the ocean easily.

Crew members aboard the R/V Roger Revelle retrieve a CTD rosette from the frigid waters of the Southern Ocean. Every bit the device is lowered into the body of water, electronic instruments measure salinity, temperature, and depth. Each of the white bottles collects seawater at different depths for detailed analysis. (Photograph ©2008 Brett longworth.)

As we fire fossil fuels and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels go upwards, the ocean absorbs more carbon dioxide to stay in balance. But this assimilation has a price: these reactions lower the water's pH, meaning it's more than acidic. And the ocean has its limits. As temperatures ascension, carbon dioxide leaks out of the ocean like a drinking glass of root beer going flat on a warm 24-hour interval. Carbonate gets used upwardly and has to exist re-stocked past upwelling of deeper waters, which are rich in carbonate dissolved from limestone and other rocks.

In the heart of the ocean, air current-driven currents bring absurd waters and fresh carbonate to the surface. The new water takes up yet more carbon to lucifer the temper, while the old water carries the carbon it has captured into the ocean.

The concentration of carbon dioxide (COii) in bounding main water (y axis) depends on the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere (shaded curves) and the temperature of the water (x axis). This simplified graph shows that every bit atmospheric CO2 increases from pre-industrial levels (blueish) to double (2X) the pre-industrial amounts (light green), the ocean CO2 concentration increases every bit well. However, as water temperature increases, its ability dissolve CO2 decreases. Global warming is expected to reduce the ocean's ability to absorb COtwo, leaving more in the atmosphere…which will lead to even higher temperatures. (Graph by Robert Simmon.)

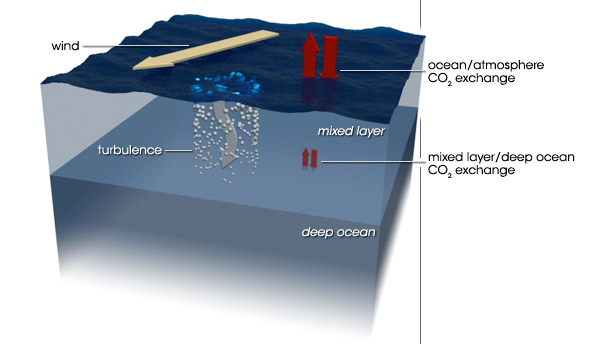

In the short term, the ocean absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide into the mixed layer, a thin layer of water with nearly compatible temperature, salinity, and dissolved gases. Current of air-driven turbulence maintains the mixed layer past stirring the water most the body of water's surface. Over the long term, carbon dioxide slowly enters the deep ocean at the bottom of the mixed layer likewise in in regions nigh the poles where cold, salty h2o sinks to the ocean depths. (NASA illustration by Robert Simmon.)

The warmer the surface water becomes, the harder it is for winds to mix the surface layers with the deeper layers. The ocean settles into layers, or stratifies. Without an infusion of fresh carbonate-rich water from below, the surface water saturates with carbon dioxide. The stagnant h2o also supports fewer phytoplankton, and carbon dioxide uptake from photosynthesis slows. In short, stratification cuts downward the corporeality of carbon the ocean can take up.

Defying Expectations

To try to understand the ocean's carbon limits, Feely and the remainder of the oceanography community measure out dissolved carbon and the ocean's pH. They probe its temperature, alkalinity, salinity, and record the presence of tracers similar chlorofluorocarbons or helium to find out when the water was final exposed to the atmosphere. By the end of a typical prowl, they will accept collected l,000 or more than measurements. And so they exit the next year to repeat it all once more, and they have done this for more than three decades.

"When nosotros started in the 70s and 80s, we had this concept: we'll measure [carbon dioxide concentrations in the ocean] x years subsequently, and nosotros'll merely see the anthropogenic input," says Feely. "We had very simplistic ideas that the anthropogenic changes would be the merely changes nosotros would see," he adds a footling ruefully.

Feely and his colleagues saw changes, simply they weren't at all the changes they expected. Carbon concentrations in the ocean did rise as atmospheric carbon dioxide skyrocketed, but in 2006, Feely and several colleagues announced that the equatorial Pacific seemed to be venting more than carbon dioxide to the temper between 1997 and 2004 than it had in previous years. And in 2007, Ute Schuster and Andrew Watson, oceanographers from the University of East Anglia, reported that corporeality of carbon that the North Atlantic Bounding main soaked up decreased by a gene of two between 1994 and 2005. The sea, or parts of it, seemed to be taking upwards less, not more, carbon.

Had the body of water already stratified, slowing the charge per unit at which it soaked up carbon? Schuster and Watson believed they saw stratification at work in the Due north Atlantic, only the drop in the amount of carbon beingness taken upwardly was too big for global warming to be interim alone. During the decade Schuster and Watson made their observations, a large-scale weather pattern, chosen the N Atlantic Oscillation, shifted.

Like El Niño in the Pacific, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) changes weather on a large scale. In the early 1990s, says Watson, the Due north Atlantic Oscillation brought stronger and more frequent winds to the northern regions of the North Atlantic during the winter. The winds stirred the body of water, tucking carbon-dioxide-laden surface water downwards and pulling unsaturated water to the surface, in event increasing the rate at which the North Atlantic took upwardly carbon. By 2000, the N Atlantic Oscillation shifted, calming winds and allowing warmer waters to aggrandize north. These two changes increased stratification in the North Atlantic and slowed the carbon uptake between 1994 and 2005, says Watson.

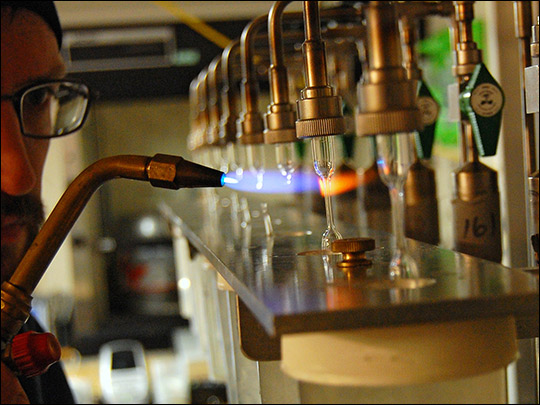

A scientist uses a torch to seal glass ampoules containing dissolved gases extracted from seawater. Tens of thousands of samples were collected during the Climate Variability and Predictability cruises. Scientists were surprised when decades of sampling revealed a complex relationship between human-made carbon dioxide emissions, cyclical changes in climate, and the oceanic carbon cycle. (Photograph ©2008 Brett longworth.)

In the Pacific, Feely tracked the increased venting at the equator to a shift in some other natural blueprint. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation is a decades-long climate pattern that alternately warms and cools the ocean. "When the Pacific Decadal Oscillation shifts into its cold phase, you become stronger winds and stronger upwelling," says Feely.

In the early 1990s, the North Atlantic Oscillation was strongly positive (green bars) during winter. In the mid-90s, the climate pattern became more variable, just overall, was weakly negative. Lower winds and college temperatures in the North Atlantic slowed carbon uptake. (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on NCAR information.)

The ocean does non take upwards carbon uniformly. It breathes, inhaling and exhaling carbon dioxide. In addition to the wind-driven currents that gently stir the middle of bounding main basins (the waters that are most limited by stratification), the ocean'due south natural, large-scale circulation drags deep h2o to the surface here and there. Having collected carbon over hundreds of years, this deep upwelling water vents carbon dioxide to the atmosphere like fume escaping through a chimney. The stronger upwelling brought by the cold phase of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation apparently enhanced the size of the chimney and let more carbon escape to the atmosphere.

In the equatorial Pacific, carbon dioxide venting increased between 1997 and 2004. This coincided with a shift in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) from a warm phase (positive) to a cool stage (negative), during which winds and upwelling of deep h2o are stronger. The graph shows the values of the PDO alphabetize every bit i-year averages (line) and five-year averages (shaded). (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on JIASO data.)

After 30 years of measurements, the ocean carbon community is realizing that tracking human being-induced changes in the ocean is not every bit easy equally they thought it would be. Information technology wasn't a mere matter of measuring changes in carbon concentrations in the ocean over time because the natural carbon cycle in the sea turned out to be a lot more variable than they imagined. "Nosotros discovered that natural processes play such an important part that the signals they generate can be as large as or larger than the anthropogenic signal," says Feely. "Now we are trying to address how these decadal changes affect the uptake of carbon. Once nosotros account for these processes, we can remove them from the data set and calculate the anthropogenic carbon dioxide as the residuum." Simply to track the increasingly complicated carbon remainder sheet, the sea customs needed models, mathematical simulations of the natural globe.

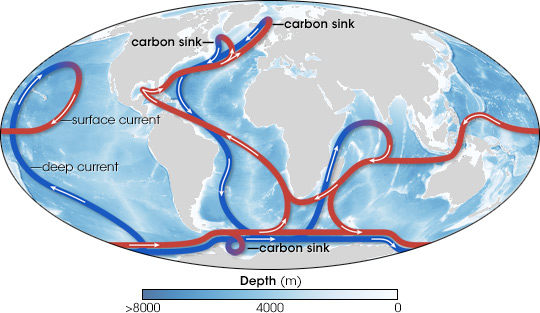

The global oceans are connected by deep currents (blue lines) and surface currents (crimson). Carbon from the atmosphere enters the ocean depths in areas of deep water formation in the N Atlantic and offshore of the Antarctic Peninsula. Where deep currents rise towards the surface, they tin can release "fossil" carbon dioxide stored centuries ago. (Map by Robert Simmon, adapted from the IPCC 2001 and Rahmstorf 2002.)

The Modeled Ocean

Rather than huddling over bottles of h2o on a ship in the center of winter, Corinne Le Quéré huddles in front of a computer screen in her office at the University of East Anglia. "I have an piece of cake life compared to the people who do observations," she notes. "I'm a modeler. I stay in my office all day." With the click of a mouse, Le Quéré gathers existent-world observations into a computer program that simulates ocean processes. The model helps scientists put together measurements like Feely's—snapshots of the ocean at specific places and times—to encounter how individual processes come up together to create the weather condition they observed. In 2007, Le Quéré announced that her model helped her uncover the first prove that man activeness is changing the ocean carbon sink.

Le Quéré and a number of colleagues were studying a natural weather cycle, the Antarctic Circumpolar Wave, which circles Antarctica in the Southern Ocean. "We were trying to meet if nosotros could detect which direction the carbon dioxide flux changed when the circumpolar wave passed through," says Le Quéré. In other words, did the phenomenon cause the ocean to take upwards more than or less carbon dioxide? Unlike Feely and other observational oceanographers who had been trying to mensurate the human impact on the ocean carbon cycle for decades, Le Quéré simply wanted to empathize how natural processes could alter the way the Southern Ocean takes carbon from the temper.

The trouble, Le Quéré found, was at that place was not enough body of water data to simulate changes in the bounding main as the Antarctic Circumpolar Moving ridge inverse. "In that location'south not very much data in the Southern Ocean considering people don't desire to become there in the winter. There's too much wind. But you demand wintertime data to get changes in the carbon sink," says Le Quéré. "I can complain that there are no data in the winter, but there'south no style I would go there myself," she adds with a laugh. Instead, Le Quéré inferred ocean carbon dioxide levels based on atmospheric measurements.

Scattered across the southern hemisphere, a number of isolated weather stations track concentrations of carbon dioxide in the temper. Many are automated, says Le Quéré, but in some cases, hardy samplers trek outside at the same time every mean solar day to pump a sample of temper into a flask, most of which are shipped to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Earth Organization Enquiry Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado. For Le Quéré, the more remote stations—in places like the South Pole, Palmer Station on the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, Amsterdam Island in the due south Indian Ocean, and Ascension Island in the South Atlantic—provided key measurements.

Corinne Le Quéré studies the carbon bicycle through calculator simulations that incorporate direct observations. (Photograph ©2008 Sheila Davies, University of East Anglia.)

In these remote places, the biggest thing changing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels is the ocean. The plants whose seasonal cycles dominate atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations in other parts of the world, just don't be in such places. "If there is one place in the world where you lot can [measure changes in the bounding main carbon sink with atmospheric measurements], it is over the Antarctic ocean," says Le Quéré. "It is the place where you lot have the least contaminated air, so to speak."

When Le Quéré plugged atmospheric measurements from the Southern Ocean between 1981 and 2004 into her model, she was startled past the result—something far more than interesting than the Antarctic Circumpolar Wave. "The Southern Ocean carbon sink has non changed at all in 25 years. That's unexpected because carbon dioxide is increasing so fast in the temper that you would expect the sink to increase too," says Le Quéré. But it hadn't. Instead, the Southern ocean held steady, while atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations climbed. Why?

Continuous measurements of the atmosphere are obtained at cold and remote observatories on the shores of the Southern Bounding main, such as Palmer Station on the Antarctic Peninsula. These atmospheric data complement the straight measurements of ocean water made during research cruises. (Photograph courtesy Jeffrey Kietzmann, National Scientific discipline Foundation.)

Le Quéré expected to see a steady increment in the amount of carbon dioxide captivated by the Southern Body of water betwixt 1981 and 2004 (blue line). Instead, weather station measurements (ruby-red line) suggested year-to-year variability, just no long-term increase over time. (Graph past Corrine Le Quéré, Academy of E Anglia.)

Humanity's Unexpected Impact

The current of air measurements that Le Quéré had entered into her model held the key. Since 1981, winds in the Antarctic ocean increased, and Le Quéré believes that the ozone hole and global warming are to blame.

"Ozone naturally warms the upper atmosphere because it captures the radiation from the Lord's day and re-emits it there," says Le Quéré. "If you deplete ozone, you get a very large cooling in the upper atmosphere." The huge temperature difference between the ozone hole and the rest of the stratosphere causes strong winds effectually Antarctica. Uneven warming in different parts of the southern hemisphere from recent global warming also created a temperature difference that strengthened the winds. The stronger winds raise deep water upwelling, which allows carbon to vent into the atmosphere from carbon-rich deep water. In essence, while the sea may exist taking up more than anthropogenic carbon to keep pace with levels in the atmosphere, it's also venting more carbon than it did in the past, and that changes the size of the overall sink.

Like Feely saw in the equatorial Pacific, stronger winds made the Southern Ocean vent more carbon dioxide in areas where deep h2o upwelled to the surface. This idea, that upwelling h2o releases carbon dioxide, ran counter to what oceanographers had believed almost stratification for decades. "When I started, everybody said if the ocean stratifies, and so it will absorb less anthropogenic CO2. Merely really now, it's not and so clear," says Le Quéré. If global warming causes upwelling areas like the high latitudes or the equatorial Pacific to stratify, then the natural carbon dioxide that is normally released during venting may just stay in the deep ocean. Stratification might current of air upwards having competing effects on the overall carbon cycle, with saturation slowing carbon dioxide uptake in surface waters, merely also suppressing venting.

The other assumption that Le Quéré's work rattled was the idea that the just fashion people would change the ocean carbon sink is through increased concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide. "At the beginning, we thought the of import aspect was the increase in atmospheric CO2," says Le Quéré. "And now, I think the changes in ocean physics [mixing] are very important too. I wouldn't exist surprised if the changes in marine ecosystems get equally important, but we just haven't seen this even so."

"The link betwixt the devastation of the ozone layer, the changing wind patterns, and the impact on the carbon bike is the thing that makes Le Quéré'south newspaper unique," says Feely. "Information technology links dorsum to man-fabricated impacts on the climate." The idea that the homo-fabricated ozone hole and global warming accept inverse the Southern Bounding main carbon sink is "agonizing on the one mitt, but extremely interesting besides," says Jorge Sarmiento, an ocean modeler and Le Quéré'due south former mentor at Princeton University.

Non surprisingly, Le Quéré'south ground-breaking work has been controversial. Two other groups take challenged her report in messages to Science, where her work was published, but Le Quéré is standing by her results. The problem is, the method of deriving the size of the bounding main sink from atmospheric carbon, non bounding main carbon, is uncertain. And like all models, Le Quéré'due south model has uncertainties of its own.

"I recollect it'south possible that the Antarctic ocean sink is slowing downward," says Sarmiento, "[Le Quéré] did a super job of bringing in all kinds of constraints on the model, only all of them accept huge uncertainties. I'1000 even so property off." Feely agrees. "In this case, modelers are leaping alee of the observationalists. What we as oceanographers want to do is make sure that in that location is a sufficient amount of oceanographic information to substantiate that. You demand thirty years of data before you can say anything, and that's an incredible feat in itself."

The key to understanding the stability of the Southern Ocean carbon sink turned out to be winds. Since the early 1980s, winds circumvoluted Antarctica steadily increased, driven by both global warming and changes in the upper atmosphere caused by the ozone pigsty. (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) data.)

And then the question remains: How is the bounding main carbon sink changing? Equally scientists try to reply the question today, they accept more tools available to them, including NASA satellites that measure the productivity of bounding main plant life, winds that stir the water'south surface, and global temperature patterns that reveal ocean circulation. And in late 2008, NASA will launch the Orbiting Carbon Observatory, which will rail the abundance and distribution of carbon in the atmosphere.

The applied science has evolved over the past decade as scientists realized that to sympathize the ocean carbon cycle, they are going to have to wait for the homo fingerprint in ocean circulation and biological science, not just in ocean chemistry. "When I started nearly 15 years agone, it was assumed that the circulation of the ocean did non change. The only matter we always thought virtually was carbon dioxide increasing in the atmosphere," says Le Quéré. "Now we have a much broader view of what is happening. I think very few people accept the steady state hypothesis anymore. That's finished."

Similar much research, Feely and Le Quéré's piece of work creates almost every bit many questions every bit answers: What other climate cycles affect the oceanic carbon sink? Will the Southern Body of water render to normal every bit Antarctic ozone recovers? Will the increasing severity of global warming finally cause much of the ocean surface to stratify? In time—with standing written report—these questions volition be answered, to exist replaced with new ones. (Photo ©2008 Brett Longworth.)

-

References

- Archer, D. (2007, November 1). Is the ocean carbon sink sinking? RealClimate. Accessed March xiii, 2008.

- Canadell, J.G., Le Quéré, C., Raupach, M., Field, C., Buitehuis, E., Ciais, P., Conway, T., Gillett, Due north., Houghton, R., and Marland, G. (2007, November xx). Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (47), 18866-18870.

- Denman, K.L., G. Brasseur, A. Chidthaisong, P. Ciais, P.M. Cox, R.E. Dickinson, D. Hauglustaine, C. Heinze, Due east. Holland, D. Jacob, U. Lohmann, Due south Ramachandran, P.L. da Silva Dias, Due south.C. Wofsy and 10. Zhang. (2007). Couplings Betwixt Changes in the Climate Organization and Biogeochemistry. In: Climate Change 2007: The Concrete Science Basis. Contribution of Working Grouping I to the Fourth Cess Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, Thou.B. Averyt, Yard.Tignor and H.Fifty. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, Uk and New York, NY, United states.

- Doney, South. (2006, March). The dangers of body of water acidification. Scientific American, 58-65.

- Feely, R., Takahashi, T., Wanninkhof, R., McPhaden, G., Cosca, C., Sutherland, S., Carr, M. (2006, Baronial 23). Decadal variability of the air-ocean COii fluxes in the equatorial Pacific. Journal of Geophysical Research, 111, C08S90.

- Feely, R., Sabine, C., Lee, K., Berelson, Westward., Kleypas, J., Fabry, V., Millero, F. (2004, July 16). Bear upon of anthropogenic CO2 on the CaCOthree system in the oceans. Science, 305, 362-371.

- Fung, I., Doney, S., Lindsay, Thou., John, J. (2005, Baronial 9). Evolution of carbon sinks in a changing climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102, 11201-11206.

- Greenblatt, J. and Sarmiento, J. (2004). Variability and climate feedback mechanisms in ocean uptake of CO2. In The Global Carbon Bicycle [Field, C. and Raupach, M., eds.], pp. 257-275. Washington: Island Printing.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climatic change. (2001) Climate Alter 2001: Synthesis Report. Geneva: Globe Meteorological System.

- Law, R., Matear, R., Francey, R. (2008, Feb 1). Comment on "Saturation of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink due to recent climate change". Scientific discipline, 319, 570.

- Le Quéré, C., Rödenbeck, C., Buitenhuis Due east., Conway, T., Langenfelds, R., Gomez, A., Labuschagne, C., Ramonet, Chiliad., Nakazawa, T., Metzl, N., Gillet, Due north., Heimann, Chiliad. (2008, February 1). Response to comments on "Saturation of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink due to recent climate modify". Science, 319, 570.

- Le Quéré, C., Rödenbeck, C., Buitenhuis E., Conway, T., Langenfelds, R., Gomez, A., Labuschagne, C., Ramonet, Thousand., Nakazawa, T., Metzl, N., Gillet, N., Heimann, Thousand. (2007, June 22). Saturation of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink due to recent climate change. Science, 316, 1735-1738; published online May xvi, 2007.

- Le Quéré, C. and Metzl, Due north. (2004). Natural processes regulating the ocean uptake of COii. In The Global Carbon Cycle [Field, C. and Raupach, M., eds.], pp. 243-255. Washington: Island Printing.

- Orr, J., Fabry, V., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Doney, S., Feely, R., Gnanadesikan, A., Gruber, N., Ishida, A., Joos, F., Key, R., Lindsay, K., Maier-Reimer, E., Matear, R., Monfray, P., Mouchet, A., Najjar, R., Plattner, G., Rodgers, K., Sabine, C., Sarmiento, J., Schlitzer, R., Slater, R., Totterdell, I., Weirig, M., Yamanaka, Y., Yool, A. (2005, September 29). Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-kickoff century and its affect on calcifying organisms. Nature, 437, 681-686.

- Rahmstorf, S. (2002). Ocean apportionment and climate during the past 120,000 years. Nature, 419, 207-214.

- Sabine, C. and Feely, R. (2007). The oceanic sink for carbon dioxide. In Greenhouse Gas Sinks [D.S. Reay, C.North. Hewitt, K.A. Smith, and J. Grace, eds.] Cambridge: CAB International.

- Sabine, C., Feely, R., Gruber, N., Key, R., Lee, K., Bullister, J., Wanninkhof, R., Wong, C., Wallace, D., Tilbrook, B., Millero, F., Peng, T., Kozyr, A., Ono, T., Rios, A. (2004, July 16). The ocean sink for anthropogenic COtwo. Science, 305, 367-371.

- Schuster, U. and Watson, A. (2007, Nov viii). A variable and decreasing sink for atmospheric CO2 in the North Atlantic. Journal of Geophysical Enquiry, 112, C11006.

- Zickfeld, Chiliad., Fyfe, J., Eby, M., Weaver, A. (2008, February 1). Annotate on "Saturation of the Southern Ocean CO2 sink due to recent climatic change". Science, 319, 570.

- Related Reading

- The Carbon Cycle, a fact sail published on NASA's Globe Observatory.

- NASA. (2007). The body of water and the carbon bicycle. Science@NASA. Accessed November 29, 2007.

- National Geographic. (2007). Our environment & oceans for life. National Geographic Education Network. Accessed Nov 29, 2007.

- Body of water Literacy Network. (2006). Sea Literacy: The essential principles of ocean sciences, M-12. Accessed Nov 29, 2007.

Source: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/OceanCarbon

0 Response to "Will Eventually Bring the Ocean Back to Equilibrium and Be Able to Absorb Co2 Again"

Publicar un comentario